The Past Is Alive: How Photos Heal Black Women

I hadn’t talked to my cousin in years. An argument and family drama damaged the closeness Becky and I shared. Both only children, three years apart in age, we were like sisters. Our late grandfather loved telling the story about a weekend I spent at Becky's house when we were children. Playing outside, we encountered neighborhood bullies. Unafraid and precocious, I screamed, “Don’t mess with my cousin. I’m from Baltimore!” Those kids never bothered us again.

Shortly after Becky and I stopped speaking, she reached out. She apologized and wanted to explain her side of things. I was stubborn, refusing to give in. Secretly, I was devastated to miss Christmases, birthdays, and other special occasions with Becky and her children.

Becky broke the ice again in early 2025 by inviting me to her son’s high school graduation. The email was an olive branch.

“I’m starting to organize Vincent’s graduation party…I hope you can come.”

Things were different now. I’d spent the last year working to support Black women, women of color, and gender expansive people of color to be empowered, compassionate leaders, exploring honest questions about their healing and well-being. We also had a new president. I couldn’t change what had occurred since he’d taken office: executive orders banning diversity, equity, and inclusion, deportations that separated families, widespread fear and chaos. But I could begin with me. I missed my cousin. And being with loved ones during this time made me feel joyful and strong. It was my own act of resistance.

I responded to Becky almost immediately.

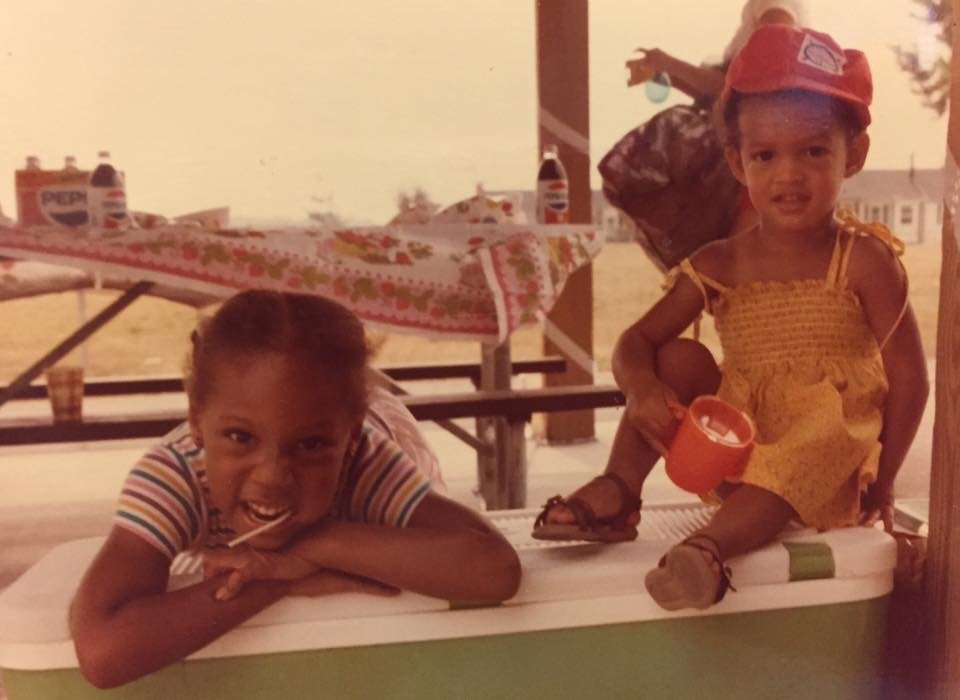

Though we live 2,000 miles apart, I learned we’d be in the same state in a few weeks. We agreed to meet for lunch. While talking, I showed Becky two pictures I’d recently found of our grandmother. One showed our thirty-something grandmother on a bike, looking young and carefree. In another, she is a sullen, red lipstick wearing teenager. I was curious about our family's past and its impact on the present.

“Have you seen these before?” I asked.

Several stories emerged as Becky examined the photos. A memory of riding bikes with our grandparents. Spotty details about our grandmother’s father. Reflections on her dad’s childhood. Becky's openness encouraged me to share, too. Over several hours, we bore witness to each other, unpacked family history, found connection and meaning.

I’ve been inspired to repeat this process with other Black women. Through in-person gatherings, we'll share photos, celebrate our ancestors, discuss stories so loved ones are remembered at a time when Black people are being actively erased from history. Invitations to these spaces have been received with enthusiasm and relief.

“I am in need of communion,” one woman said.

Another responded, “This is the sanctuary my soul needs.”

Today, Becky and I text and call each other often—sometimes talking for hours at a time. We not only repaired our relationship; we are encouraging other Black women through the Toogood Stories project to tell their family histories and do the work of intergenerational healing.