Podcast as Community: A Conversation with Michelle Dahlenburg and Bojan Fürst

Joe Lambert interviews Bojan Fürst and Michelle Dahlenburg.

Preserving Every Voice: A Conversation with Marcela Tripoli of the Museum of the Person

Joe Lambert interviews Marcela Tripoli, Museum of the Person

Mapmaking for Hope and Change - An Interview with Ellen Delgado, ESRI StoryMaps

Joe Lambert interviews Ellen Delgado, ESRI StoryMaps

Making A Difference - StoryCenter's Joe Lambert Interviews Marita Jones and Tina Tso, Healthy Native Communities Partnership, Shiprock, New Mexico

Joe Lambert interviews Marita Jones and Tina Tso from Healthy Native Communities of Shiprock, NM.

Let's Live Together - StoryCenter's Joe Lambert Interviews Human Rights Lawyer Jennifer Harbury

Proponents and doomsayers have lined up in the face of the breakthrough of these large language model and deep learning computing engines. How will these developments affect digital storytelling as a community of practices?

AI and Digital Storytelling - StoryCenter's Joe Lambert Interviews Brian Alexander, Georgetown University

Proponents and doomsayers have lined up in the face of the breakthrough of these large language model and deep learning computing engines. How will these developments affect digital storytelling as a community of practices?

Grounding the Telling of Others' Stories in Ethical Practice: An Interview with Syrga Kanatbek Kyzy

My very first interviews were exciting, and people’s reactions were better than I expected: supportive and proud. But after reading those interviews, I realized that I was leaving out important parts of my journey—mainly, the challenges I had faced.

Stories in Motion: How Stories Shape Our Relationship With Space

Through this workshop, we learned more about the connection people make between stories and maps, about the process of story mapping, and also about how to use new technology and create trust and a safe space through digital communication tools.

Digital Documentation and Storytelling Build Greater Appreciation for Jordan’s Cultural Heritage

This community-centered documentation project and virtual tour in Madaba serves as a public education tool, supports the livelihoods of Madaba residents, and provides a digital inventory of the site until the project team can return and complete its work in the museum.

StoryCenter Enters the World of Podcasting

For thirty years, StoryCenter has supported people in sharing their own stories, in their own words. As our efforts have grown and evolved, storytelling technologies have gotten cheaper and increasingly accessible, and podcasts are everywhere. Now, we’re excited to announce what feels like a natural next step for our work: a full-fledged podcasting initiative. In this post, our Director of Podcasting Ryan Trauman describes what we’re doing.

Where the Stories of the Pandemic Will Live

Somehow, we forgot the last pandemic. The 1918 flu was conspicuously downplayed in medical records, did not fill the pages of the newspapers, and was omitted from personal journals. We cannot locate the cacophony of beleaguered voices; we will never know what they felt, what the flu did to them. There are theories as to why: it was upstaged by the horrors of WWI; it pulled the rug from under the belief in the advancement of medicine; it was too overwhelming to reiterate. Citizens, soldiers, doctors, they did not want to face it, or couldn’t. Why extend the dastardly thing’s lifespan by writing it down?

Addressing Broken Systems Through the Lens of the Personal: A Recovery Journey

It is my story as a mother of an addict, one tiny part. Just as I am not interested in knowing all the details of his time spent making his bed out in the cold (to quote John Martyn’s May You Never), I don't expect him to be interested in knowing the agony of my waiting. Or the enormity of this expedition.

Storytelling to Address Housing Disparities in Chaffee County, CO

It turns out that humans live in houses—if they’re lucky. And our conversation about housing has turned to those humans. How much we value them. How much we need them in our community, and how much their voices matter. And that absolutely changes the conversation about housing.

Making the Tech Disappear, in Online Education

No one has ever tried this all-online schooling thing with little kids before. There aren’t any experts. And now, the schools are trying to figure out the human interaction on an impossible timeline, with no room for training teachers on how to hold a class of nine year olds safe and engaged in an online space. The thing that amazes me about StoryCenter, over and over, is that you all have figured out how to make the tech essentially disappear, in service of deeply human work.

2019 In Review: Celebrating Our Year in Storytelling!

A selection of projects we’re especially proud of in 2019.

Nurstory: Incredible Experiences of Digital Storytelling

As if by magic, by day three of the workshop, I created a digital story about resilience. Then, at the end of the workshop, a screening of all the group members’ videos occurred. It was breathtaking. What an experience! I immediately knew I wanted to do it again–someday.

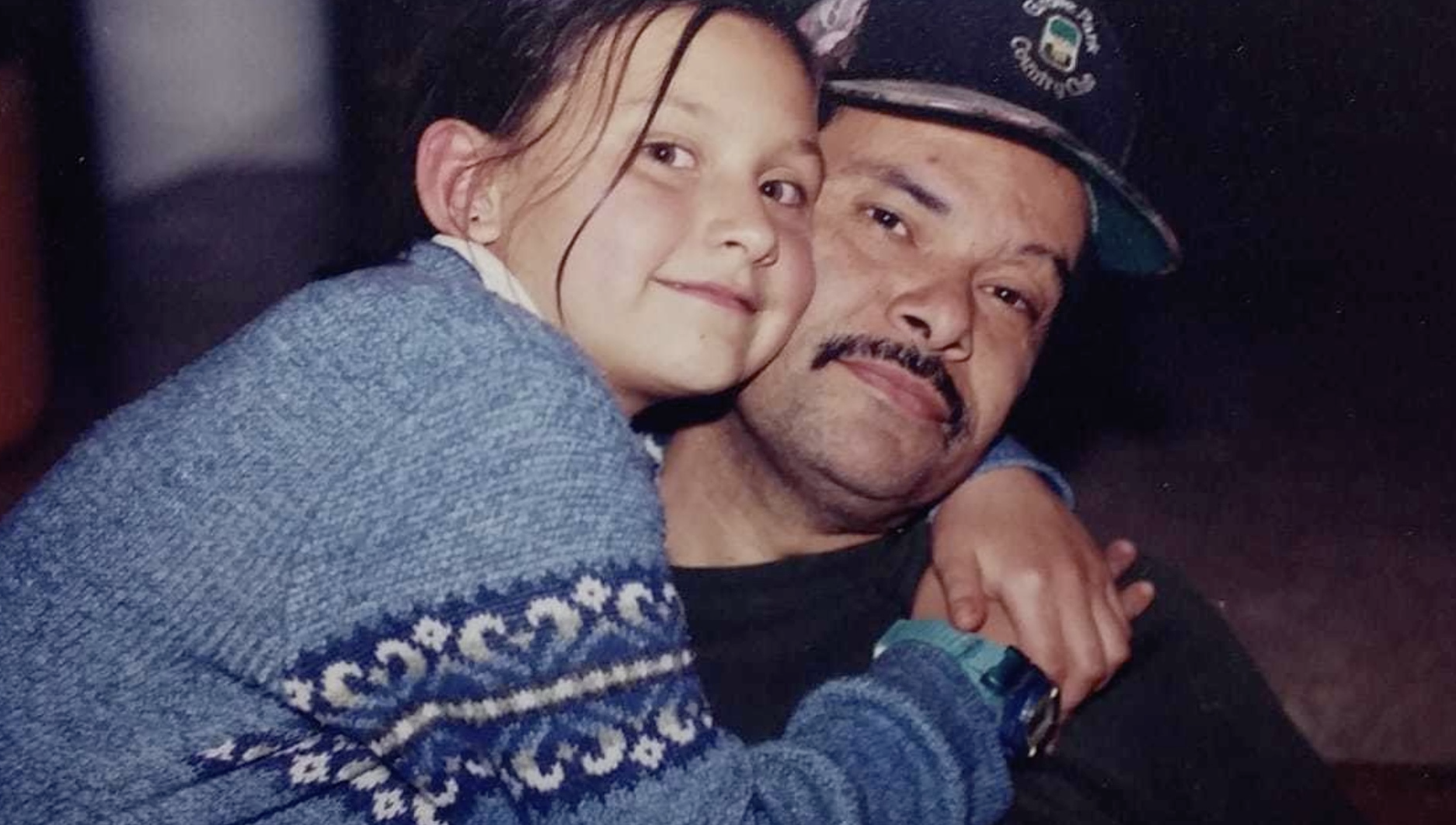

Motivation

Sometimes, when I think about the control that was stolen from my mother at such a young age, I want to hold her and mourn with her. But, that's not a place we can go. Sometimes, when I uncover a new scar or tenderness in my life based on what happened to me, I want to reach out to her. But, that's not a place we can go.

St. James Parish Rising: Documenting a Legacy of Environmental Racism in Louisiana

I was born in St. James Parish when Jim Crow still ruled. Racist laws made sure that many black Louisianans were unable to participate in democracy. It has been more than 50 years since the passage of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act, but those of us in the 5th district were not informed when in 2014, the northern part of the district was re-zoned for industrial use. While white residents sold their properties and moved away, black residents did not receive buy-out offers. We were left inhaling the toxic air produced by the invading petrochemical plants.

Remember, Re-Story, Re-Build: Listening to the California Wildfire Story Collection

Three years ago I know I appreciated the role libraries played in our local communities, but after this extended campaign with California Listens, and in particular listening to the some 50 stories coming out of the Wildfire project, I see that along with religious, educational, and psychological support environments, libraries are a critical sanctuary in times like these.

Building Empathy in Local Communities: The Redwood City 2020 Digital Storytelling Project

Having such a comforting setting allowed us to be open when sharing our story ideas as a group and getting feedback. All the storytellers did an amazing job of capturing our community’s values and welcoming environment. They crafted stories about family, identity, the struggles of immigration, and many other topics.