Sowing Equity: An Interview with the Backyard Gardeners' Network

The week before Christmas, Executive Director Joe Lambert had a chance to speak with Jenga Mwendo and Courtney Cocoamo Clark of the Backyard Gardener’s Network (BGN). Established in 2009, BGN has become a critical resource for the predominately African American Lower Ninth Community in New Orleans. Having had the fortune to work in New Orleans actively over the last dozen years, Joe recognized the Lower Ninth as the heart of the city, a heart that was broken when the levy’s breached in two spots along the intercoastal canal during Hurricane Katrina. The area north of Claiborne Avenue was almost completely decimated by the effects of the breach, and the reconstruction of the larger part of the neighborhood has been slow and difficult. But projects like BGN show how deeply residents care, and the innovative ways they are creating a stronger post-Katrina culture.

Joe Lambert: What is Backyard Gardener's Network and what role does it play in New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward community?.

Jenga Mwendo: Backyard Gardener's Network was founded in 2009, around the idea that we have a strong, cultural tradition of growing food in our community. We can use that as a community building tool, especially after we've experienced so much loss following the levy breach from Hurricane Katrina and lost so many people, so much property, and damage in our community, including many businesses.

I saw Backyard Gardener's Network as one way we can help build our community back together by reconnecting people around something that we all have some connection to, whether it be people who grow things in their backyard, which there's still quite a few people who do that, or people who remember their parents or their grandparents doing it, or their neighbors would share vegetables with each other and produce with each other, or just people who eat food.

Everybody likes to eat. There's so many different ways that we can connect around food and growing food. We want to build on this concept as a way to bring our community closer together. We want to honor and respect the knowledge and the resources that we have in our community to make our community a better place.

Joe: Courtney, you were born and raised in this neighborhood, what does BGN’s work mean to the community members such as yourself?

Courtney Cocoamo Clark: When I first experienced the Backyard Gardener's Network, I was a volunteer painting faces at events. I saw it definitely as a great community and gathering spot. A great place for people in the community to network with each other and talk with each other. You could run into people that had returned to the community (after the displacement) that you may not have known were back.

After Katrina, as people came back there were neighbors who may have been right next door or right across the street, but when they returned, they might have ended up on the other side of the ward. BGN was a place to catch up.

The Lower Ninth Ward is definitely a place where a lot of its community members are family. If they're not born into the same family, they become family because everyone knows each other. The Backyard Gardener's Network gave us a central location to come back together again, It gave us a great place to get back to that sense of community gathering that we've always had.

Joe: Can you just give us an idea of your programs? From what I've seen, it has a big emphasis on multiple generations.

Jenga: It varies. We have three main programs that we do. We do a Kid's Club on Fridays. We do a Food is Medicine workshop series on Thursdays for two months each season. We do a monthly Super Saturday Community Party. Each of those have different levels of participation, different age groups, and different activities going on.

At our last Super Saturday, which was also our closing celebration at the Garden to close out the season, we had about seventy-five people at the Garden. Courtney, is that about right?

Courtney: That sounds about accurate. One thing we did different at this event was we had a DJ. We had quite a few people that just came in once they heard the music going. They heard the music, they saw everything going on, and kind of bee-lined for the food. So we could have had a good hundred people in there, coming in and out. It was a beautiful day that day.

Jenga: We'll prepare a potluck of foods for people. Then we'll have like a mini-market. We invite local vendors to come and set up and sell what they make. We also had a face painter this time. We really just want to bring as many people and as many different age groups and people from our community to come to the Garden, as a sort of mini-festival. While we didn’t do it at the last event, we'll have gardening workshops as well, so people who are interested can learn more about how to plant their own garden. Courtney, you can talk about Kid's Club?

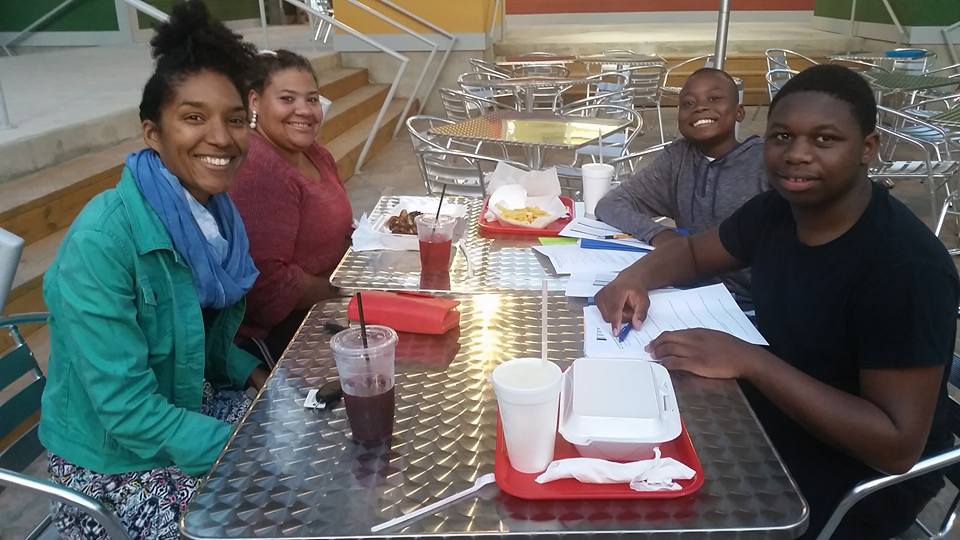

Courtney: The Kid's Club is something that we offer to the kids in the community on Fridays as well as on home days from school. We work with them on different subjects such as the ecosystem, art, the garden aspect of planting a garden, actually harvesting and cooking from the garden. We work with mainly 'elementary school age children, and some junior high school youth as well.

Then we also have our Youth Internship Program, which our teenagers between the ages of fourteen and nineteen. They learn more about gardening as well as doing outreach and learning how to develop a business, how to manage money, and develop ways of doing outreach and sales. These activities are seasonal as well through the Spring into the Summer and Fall.

We have our Food is Medicine program, which is where people in our community come and they learn to eat cleaner and healthier, as well as learning about the nutrition from doctors and nutritionists. Health educators, from herbalists and health professionals of all different genres, come into to teach residents how to cook and eat healthier. We have a serious problem with diabetes, high blood pressure, cholesterol, and obesity in the Lower Ninth Ward. Food is Medicine is a way for them to learn different ways of possibly eating the same foods that they already eat, but healthier and cleaner so they can possibly turn around their conditions.

Jenga: It is in the mix of programs that we get our connection with the different generations. The Kid's Club, and the interns that work with the Kid's Club, and the Super Saturday which covers everyone, people our age, the kids, and the seniors. We also have the seniors who participate in all of our functions. Everything overlaps and it's very important to get all of those generations involved.

I think this is important, one because our community is made up of all generations. From the beginning, we never wanted this to be something that was only for kids, or only for seniors, or only for adults. We felt like it was very important to foster those inter-generational connections. We also feel from a practical sense it's important to involved all ages because our younger people, hopefully, will be the ones carrying on Backyard Gardener's Network in the future. They will be rising into leadership positions as we move along. And of course our older people, the parents or the grandparents, are the ones who are telling their teenagers, "Go sign up for this program."

Joe: Absolutely. Do you want to add something to that, Courtney?

Courtney: I always feel that our senior generation is our past that keeps everything going. Our middle generation, which is us, Jenga and I, we are still learning from them. As well as our youth, our teenagers and our kids, learning from us, but also teaching the middle generation and the senior generation what's up and coming. We all learn and teach each other and keep the whole cycle going as far as what we're learning. The seniors forget some of the things that they've already learned when it comes to gardening skills, but then it comes to them as we remind them, and they re-teach us little secrets and skills that we didn't know. The teenagers have their own innovative ideas and they can teach those ideas to all of us. The children, they're just so enthusiastic about learning anything. hey definitely will suck it in like a sponge. That's definitely what's important at the Garden as well as in our community.

Joe: Well said. That's well said. The transition here is to think about how much has happened since the levies broken, how much that neighborhood in particular was tortured by the event in a way that was very profound. I remember touring it just a month after the levies broke and being just in tears, frankly, about what happened and what it looked like, and that it was all avoidable, and that it all may have been purposeful makes it even sadder. You guys are literally replanting and reclaiming part of the Lower Ninth. Why do you think it's important that organizations like yours exist in the Lower Ninth as part of building the resilient identity for that community and for greater New Orleans in this decade since the tragedy of Katrina?

Jenga: There's a number of different thoughts I have. Number one, we have to do it because nobody else is going to do it for us. Unfortunately. We did not get the help that we needed and it really was these grassroots and non-profit organizations and volunteers, thousands and thousands and thousands of volunteers, mostly from other places, who really helped to rebuild the Lower Nine and get it back to where it needs to be.

Second, I think that the flip side of that is this is our community. We need to be in leadership positions in determining what happens in our neighborhood. For me, that was really important and continues to be really important with Backyard Gardener's Network, is one of our core values that our leadership reflects the majority of our community, which is African American, mostly low income, low to middle income African Americans. It's very important that we demonstrate that what we're doing is internal, it's home-grown, it's the community coming together and saying, "This is what we want. We want one fewer vacant lots in our neighborhood." We can actually take that lot and turn it into something that can be useful, beautiful, and productive for us. We came together and we did it. I think it's important in that sense as well.

Then, finally, the broad sense of why community organizations like ours are important in any community is because we need to have, for our kids, more positive, engaging things for them to be involved in, for them to be able to connect back with the earth and understand where our food comes from, the importance and the value of the food, the knowledge that the elders have to teach. For our adults and our seniors, to have that support for living well and eating well. To be able to do that in a beautiful garden space that our community came together to create, I think. I think those are the three.

Joe: Courtney, do you want to add to that?

Courtney: Being a lifelong resident of this community, an organization like BGN lets the powers that be know that just because you're not going to help us does not mean that we're just going to stand by and not be helped. We can stand on our own feet and help ourselves and find ways to get others to support us, whether you support us or not. That's one of the things that a lot of small organizations in other communities, as well as the Lower Ninth Ward, are letting everyone know, "Hey, we're here. Just because you forgot about us, we're going to keep reminding you that we are still here and we need the things that we need."

Jenga: Absolutely. I should add we're definitely still rely on grant funding and resources from outside, but the value of local community leadership is central to our work.

Joe: Before we finish, I want to ask about the larger Food Justice movement, and how your work fits into that discussion here in the United States.

Jenga: Yeah, I've had a lot of conversations around Food Justice and Food Sovereignty. I think where we fit in with Backyard Gardens. We've never had the intention of being a farm or doing urban farming and growing food for our community. This is a very, very valuable thing, but there's other organizations doing that. Where we focus is around the culture, around an active culture of growing food and normalizing it … again. We want to support and encourage people to do it for themselves, to do it for ourselves, which is extremely important in a neighborhood like the Lower Nine that doesn't have proper access to food. It's very difficult, especially if you don't have a car, to get around and get the things that you need. I think growing food is a great way to supplement that.

Honestly, that's the essence of Food Sovereignty: when you're growing your own food, you're controlling the production of your food, you're controlling everything about it. To me, that also ties in to land ownership.

The Lower Nine once had the highest Black home ownership rate in the entire city and one of the highest around the country, over sixty-five percent. I think the tragedy is that so many people lost not just their homes, but their property, their land. If you have land, you can build a house on it, you can grow food on it. It's yours and no one can tell you to leave.

I think we play sort of a small part in the larger picture of the food justice efforts. For me, it's very important for our community to honor positive, cultural values and the idea of self-reliance, the idea of health and close-knit community. During our programming, we've never really called out issues of Food Justice, or even really used that terminology, except with our youth interns. But it is there.

I led a training this past season that was specifically about Food Justice so the kids could understand the concepts. I feel like we're teaching the essence of Food Justice through influencing or reintegrating this idea of valuing quality food as a cultural tradition.

Courtney: Well, I agree with what Jenga was saying about the land ownership in this community. For example, my mother passed away in 2007 so I inherited the home that I live in. My neighbor has returned. I am fortunate enough that all of my neighbors within my block are all the same neighbors that I grew up with. That's the same neighbors that my children are going to know because I'm raising my children in the same idea of what my mother raised me.

But the neighbors that I had in the blocks behind me are no longer there. It's just empty lots. There are wonderful things that could possibly happen with those lots as far as expanding, growing your own food.

When I was a child, we used to have a supermarket down here. It was a small supermarket, but it was a supermarket. It wasn't one of these fast, little places where they might have a few apples and a few oranges. You have to buy whatever's there because that's all that's available.

My neighbor, she still has fruit and vegetables in her garden. My garden, since Katrina, the yard, the dirt, has changed. I, in turn, have a little garden at the Backyard Garden, which that made possible for me. As far as Food Justice, I feel like that is one of the things we're working towards. Backyard Gardener's Network is doing its part by teaching people within our community to give back to their roots as far as planting in the ground, even if it's a rental garden. Plant something.

if you plant something with a child, if they stuck their fingers in that dirt and planted it, they will eat it, because they're like, "I grew this." If we can get at least half the people in the community to do that, it will prove to everyone that, "Okay, you don't want to give us any supermarkets, but we are going to show you that we can be self-sustainable even if you're not going to assist us in this way."

Joe: Finally, can you share your thoughts about the importance of listening and storytelling in your work?

Jenga: One thing that's always been very important to me is we never tell anybody what they should do, or that what they're doing is wrong or anything. It's not about forcing people to do anything different. I think part of developing what we've done comes from listening to people and their stories.

I always think back in terms of stories. A long time ago we did a fruit tree giveaway. It was maybe in 2008 or 2009. I remember before the trees even got to the Garden, we had a line of people waiting outside to get their trees. I was like, "How did you all even find out about this?"

As they came into the Garden and started choosing their trees, the stories just started. This is what happens naturally when people get together in the Garden, especially older people. They started talking about how when they were growing up, they didn't really go to the candy store. They would just walk up and down the street and pick fruit off of trees. There would be blackberry vines growing wild so they would get blackberries. Then started telling stories about how during a flood there used to be crayfish you could pick find in a ditch. Peppergrass used to grow on the banks of the canal.

You listen and you're like, "Oh, okay." This was part of the fabric of our community's lives. This could be seen as nostalgia, but I feel like we don't always take enough time to really lift up those stories and give them respect. Because if you do you realize the stories tell us the importance of being able to rely on your environment for your food. That is something we probably took for granted.

So when convenience stores and supermarkets came, for practical and understandable reasons, we didn't need to work as hard to grow our own food. I think we missed out. If we can kind of reintegrate that back into the culture, then when then next tragedy, or set back like a large hurricane comes, it'll be easier for us to bounce back because we're already familiar with what it takes to sustain ourselves.

Courtney: My mom always told me stories of how she grew up. They actually never even bough fruit and vegetables from the market. The only thing they ever got from the market was meat. My grandmother used to make the bread. She used to get all the vegetables and the fruit from either their garden that they had in the backyard or from other people in the community and they would share fruit and vegetables. Even when I was young as a child, everybody in the community were still going to the same man to get their fruits and vegatables, we would always get our green beans and okra.

That's one of the things that the community used to do. Everybody just shared. There really wasn't a great need for a large supermarket within the community, because everybody was growing their own vegetables within the community. Now that I'm older, my children watch me struggle going to the market to get fresh fruits and vegatables- because I am one of those people who does not have a car. My children won't eat stuff which comes in a can, which is a blessing. They watch me work hard to get good food and so I believe their story is going to be different from what my and my mom's story had been.

Another way I think about listening is in our Food is Medicine program. I listen to all of the people who participate. They all have different stories. We have a couple of people who don't eat meat. They come to Food is Medicine to learn different ways of cooking and where they have to go to find those fresh foods which are not being grown by them.

Everybody has their story. My story is I want to live past the age of sixty-two, which is the age that my mom died because of all these ailments that have become quite common in our community. I feel like if we get back to that way when my grandmother was raising her kids, all of these people who are now eighty and ninety and a hundred that are still living because of those old ways. If we get back to those old ways, we'll have this long life that that story came from. That's what I know.

Joe: Thank you both for your work, and your thoughts, and we look forward to working with you this summer in capturing stories from your community.